Between Stars And Women

Meeting, 2006, oil on canvas, 70 x 70 cm.

“The Viennese exhibition was opened by three diptychs depicting women: Zarah Leander at Her Zenith, Antonina Traczyk: Avant-garde Bricklayer, and Captain Blood’s Exhibition. Highly suggestive and slightly surreal, they were palimpsests of historical, anthropological and anecdotal layers. Their protagonists – a part-Jewish actress becoming the Third Reich’s leading movie star; a female master bricklayer and communism’s unknown icon (a figure complementary to the protagonist of Andrzej Wajda’s Man of Marble); and a Papuan woman discovered by a European exhibition as she simultaneously breastfeeds an infant and a baby piglet – are female emblems of the paradoxes of history. But also – besides the underlying violence – of its infinity and undiscovered meanings. It is probably by no accident they are symbolised here by women, the ‘friends of cosmos’ (an image of it forms part of Zarah Leander), always stranger. Their lives often have non-linear meanings, and they can be a symbol of opening.”

Agata Araszkiewicz, “Near Catastrophe”, in Adam Adach. Portraits. Mirrors, 2007

Zarah Leander at Her Zenith, 2006, oil on canvas, 2 parts, 90 x 145 cm, 90 x 70 cm.

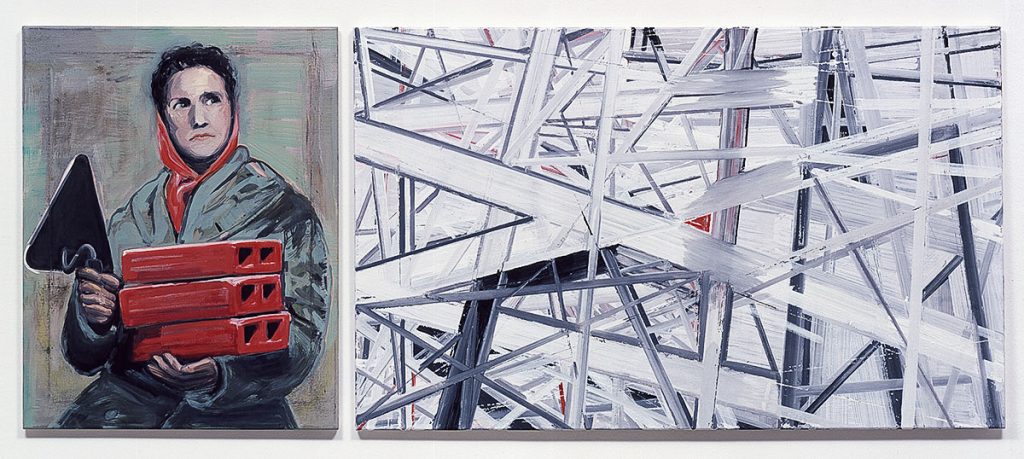

“(…) In his diptych “Antonina Traczyk, avant-garde bricklayer”, we find echoes of Aelita, this time in an heiress of the film’s real political message. In 1947, Antonina Traczyk became the first Polish woman bricklayer, making her a major representative of socially constructive work, for she exercised not only a man’s trade but also one that epitomizes construction.

Antonina Traczyk, Avant-Gard Bricklayer, 2006, oil on canvas, 2 parts, 90 x 145 cm, 90 x 70 cm.

“She earned less than her male colleagues and yet she often laid twice as many bricks as they did. Eyes riveted upwards, the left arm holding three bricks as easily as a bunch of flowers, Antonina Traczyk proudly exhibits her bricklayer’s trowel. Like a proletarian diva, she is made sublime by Adam Adach, who nonetheless totally deconstructs, in the second part of the diptych, the orthogonal philosophy of civil construction along with the portrait’s artificial realism. We find overlapping diagonal lines as far as the eyes can see. The only point in common with the portrait of Antonina is a small red triangle at the intersection of these lines, a reminder of the form of her trowel. Adam Adach found Antonina Traczyk, torn and lying on the ground at the Kolo flea market in Warsaw, on the cover of an old edition of Przyaciólka magazine.

“(…) In the diptych “Zarah Leander at her zenith”, Adam Adach paints the portrait of the actress and singer who saw Marlene Dietrich and other rivals leave, but remained stubbornly in Germany throughout World War Two and became the uncontested Diva of the Third Reich. Since she was Swedish, and with Jewish blood in her veins, Zarah Leander was first persecuted by Joseph Goebbels, who of course would have preferred a star of pure German blood as the top name at the UFA. When she was asked, “Isn’t Zarah a Jewish name?” she replied “Isn’t Joseph a Jewish name?” That put an end to the interrogation because all men worshipped her, including the Fuhrer. Zarah Leander got her zenith, which Adam Adach’s diptych materializes in a cosmological abstraction. Alas, the beauty and glamour of the Third Reich’s Diva served to detract attention from the atrocities of Hitler’s regime. Playing the femme fatale in politically innocuous romantic comedies and musicals, Zarah Leander had power at least on a level with Nazi propaganda. Her deep, almost masculine voice lifted German spirits despite her foreign accent and she was listened to on the radio everywhere, including in concentration camps. She returned to Sweden, was ostracized, but finally pardoned – for the image of Zarah Leander (…) has retained its power to fascinate. This fascination once again rubs up against the fragile wall of repulsion.

“Adam Adach alludes explicitly to anthropology with another female effigy in a figurative and abstract diptych. In “Captain Blood’s Expedition,” a Papuan mother breastfeeds a piglet at the same time as her baby. This anonymous woman seems to carry an ecological message about charity to animals and harmony between man and Nature in tribal societies. In appearance, this reading through rose-colored glasses is not disrupted by the abstract element composed of a white circle on a yellow background and a few rods. Yet all is not as idyllic as it seems. The Papuan mother is not the slightest bit interested in the well being of the piglet, whose status as food prevails over any other. Such was the conclusion of an ornithological and anthropological expedition to New Guinea financed in 1955 by an Australian millionaire and led by Captain Ned Blood, head of the agricultural station at Nondgul. Hanging head down in the burning sun after being thrown around during hours of transport, black pigs destined to be eaten, started letting out a few groans of protest but ended up giving in, eyes closed, to apathy, pain and flies. Shocked, Captain Blood tried to buy them to put them out of their misery but in vain. Behind the apparent kindness, the piglet fed at the breast of a human mother could only become an icon of savagery. (…)”

Frederico D. Rosa, “The world of Zarah Leander, Captain Blood and Antonina Traczyk”, in Adam Adach. Portraits. Mirrors, 2007

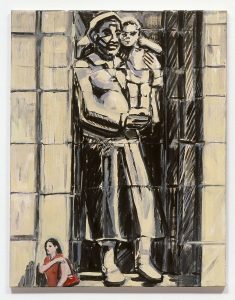

Marching Josef Sigalin District, 2006, oil on canvas, 90 x 70 cm.