Witches’ Sparks

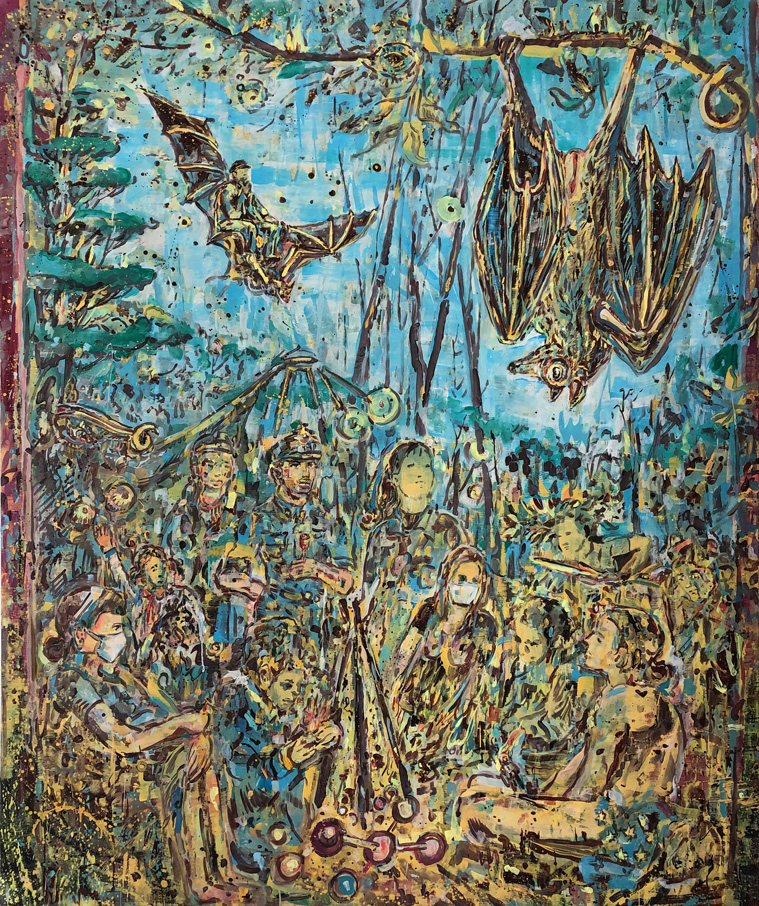

Inspired, among other sources, by the reading of Mona Chollet’s Sorcières. La Puissance invaincue des femmes (Witches. The Undefeated Power of Women, 2018), Adach subverts the classical construction of his own stroke, incorporates corporality and deliberately oscillates between emotion and kitsch, rationality and ecstasy.

“In fact, it is precisely because witch hunts tell us about our world that we have excellent reasons not to look them in the face. To risk it is to confront the most desperate face of humanity.”

Mona Chollet, Sorcières. La Puissance invaincue des femmes, 2018.

“The figure of the witch today is also subject to a new type of conflict. For some, she is a symbol of a liberated woman, an icon of feminism. For others, she represents an example of the identification of women with the stereotype of being unreasonable, unscientific, superstitious, or even, excessively earthly and corporeal. In spite of the technological advancements of our age, popular interest in magic has not changed. In fact, magic often serves as an escape from an overly technological world, where contact is mediated through science and devices. It is also a channel for standing against the negative effects of modernisation, which has led to climate change, environmental catastrophe, and cruelty towards millions of humans and animals.

Zofia Krawiec, I Will Put My Soul into the Magic Storm (exhibition), 2020.

“I would suggest that postmemory is not strictly an identity position, but rather a generational structure of transmission embedded in multiple forms of mediation.”

Marianne Hirsch, “Connective Arts of Postmemory”, 2019.

Memory Lamp was conceived during the 2020 lockdown in the spirit of “art in the time of Covid-19”. The installation (as well as the subsequent photograph in the artist’s flat during his confinement) is a tribute to the Steilneset memorial in Vardó, northern Norway. Envisioned by architect Peter Zumthor in cooperation with Louise Bourgeois, the memorial was built in 2011 to safeguard the memory and restore the dignity of the 91 victims (76 women and 15 men) burned at the stake more than three hundred years ago. Despite the simplicity and the handcrafted aspect of Adach’s objet d’art, it succeeds in translating both the gravity and the poetry of the flames as they are reflected in the surrounding mirrors. Memory Lamp was presented in different places, such as a well in a garden at night, or during a performance in the alternative art space Curie-City-Warsaw-Bauhaus.

“Commemorative artistic practices can themselves function as the connective tissue between divergent but related histories of violence and their transmission across generations. The arts offer a fruitful platform to practice the openness and responsiveness that allow such connections to emerge for the postgenerations. What aesthetic and institutional structures, what tropes and technologies best mediate the complex psychology of postmemory, the continuities and discontinuities between generations, and between proximate and more distant witnesses?”

Marianne Hirsch, “Connective Arts of Postmemory”, 2019.