Demos & Demons

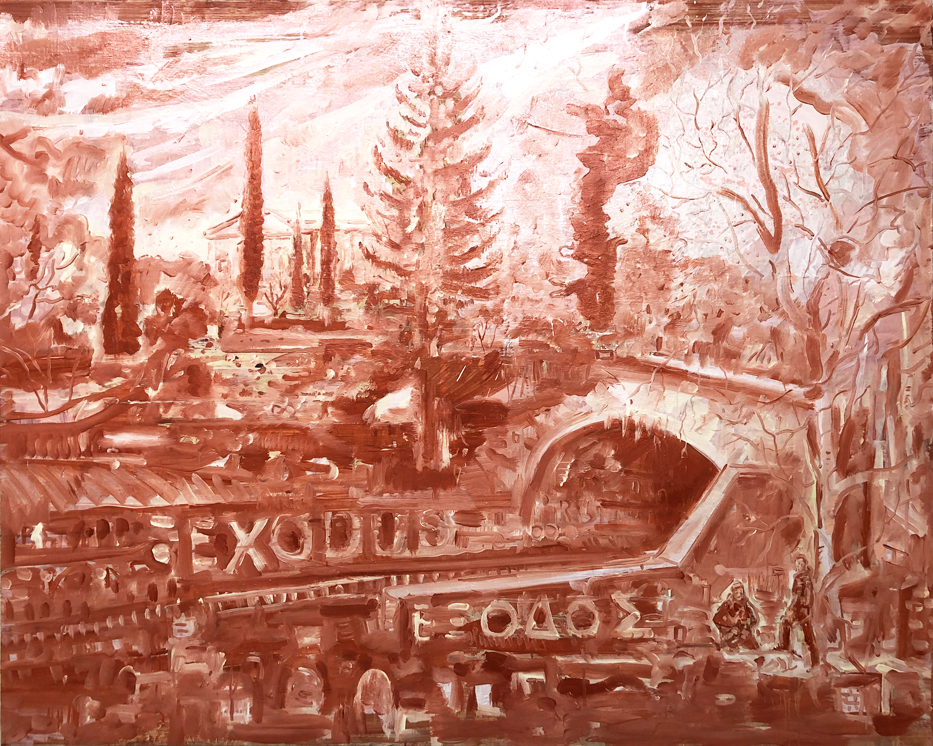

Exodus, 2021, oil on canvas, 140 x 170 cm

Athens, january 2018. As I walk along the Parthenon, my guide stops to contemplate the horizon with a mixture of pride and despair in her eyes. Then she says : « The barbarians are back. » Her words ignited my imagination. What Europe exactly was being invaded according to this aged Greek lady with a vast store of anecdotes on the godly and human misdoings of classical Greece? Christian or secular Europe? Democratic or populist? The paradoxical nature of these questions further emerged when I recalled recent debates on Europe’s dechristianisation vs. rechristianisation.

As Kenan Malik puts it : « The reason for challenging the crass alarmism about the decline of Christianity is not simply to lay to rest the myths and misconceptions about the Christian tradition. It is also because that alarmism is itself undermining the very values – tolerance, equal treatment, universal rights – for the defence of which we supposedly need a Christian Europe. The erosion of Christianity will not necessarily lead to the erosion of such values. The crass defence of ‘Christian Europe’ against the supposed barbarian hordes may well do. » Kenan Malik, « The Many Roots of Christian Europe », dans Pandaemonium (https://kenanmalik.wordpress.com/2014/03/02/the-many-roots-of-christian-europe/ ; accessed 2018-07-06)

A pandaemonium indeed : an old/new world where genealogies keep being twisted in accordance to current demonologies, if necessary to the detriment of the pre-Christian foundations of democracy. I wondered about the uses, the manipulations, both ideological and visual, of Ancient Greece, as I stopped contemplating the horizon myself. « Yes, you’re right. The barbarians are back. » But my barbarians and hers were not the same.

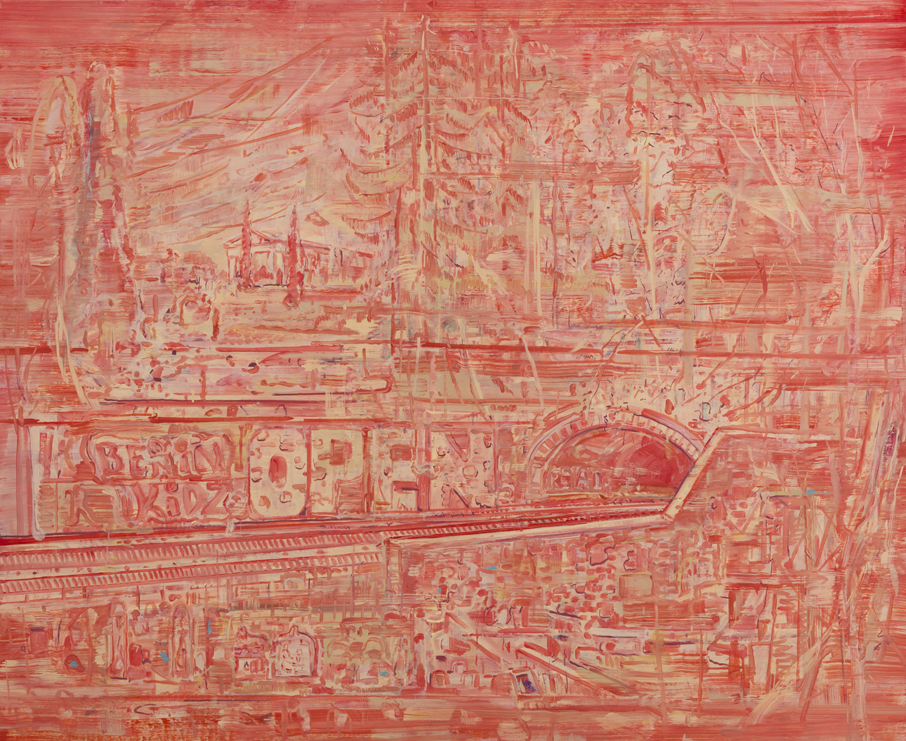

“Athens Empty Train (The Troubles of Hephaestus)”

I began working on this piece when I was in Athens. One day, as I was walking through the city, I came upon a place where I had a full view of the entire 2,500 year-old temple of Hephaestus.

I thought about how Hephaestus, blacksmith to the gods and patron of metallurgy, could be related to the current European politics. He was the one who manufactured a scepter and lightning for Zeus, as well as arrows for both war and Eros, which is why he was later held responsible for setting hearts on fire and ‘crimes of passion’. At the same time, because he made Pandora’s box out of clay and not metal, he might as well be deemed responsible for all the evil that was cast onto the world when the box was destroyed. I thought that today’s strategies of shifting blame when things go wrong echoe the ways of distorting the Greek legacy, judging the past and singling out a scapegoat, whether Pandora or Hephaestus.

The ruins of an old cemetery lay before the temple on the hill, with a train track behind it. There is a wall covered in graffiti in sight, with the words ‘Berlin Kids – OPEN’ scrawled across it.

It might have been a reference to the current migration policy or an expression of nostalgia for a better quality of life in Western Europe.

Athens Empty Train (The Troubles of Hephaestus), 2018, oil on canvas, 140 x 170 cm

The train, as it disappears into an underground tunnel, is heading north, to ‘a better world’, or, as they said in Ancient Greece, going beyond the gate of Hades.

Prior to my visit to Athens, which was during the off-season, a friend gave me her favourite Aldous Huxley quote to consider:

“I never could get much satisfaction out of meaningless discourse”, Mr. Proper continued. “I like the words I use to bear some relation to facts. That’s why I’m interested in eternity – psychological eternity. Because it’s a fact.”

“For you, perhaps”, said Jeremy in a tone which implied that more civilized people didn’t suffer from these hallucinations.

“For anyone who chooses to fulfil the conditions under which it can be experienced.”

“And why should anyone choose to fulfil them?”

“Why should anyone choose to go to Athens to see the Parthenon? Because it’s worth the bother. And the same is true of eternity. The experience of timeless good is worth all the trouble it involved.”

“ ‘Timeless good’ “, Jeremy repeated with distaste. “I don’t know what the words mean.”

“Why should you?” said Mr. Propter. “One doesn’t know the full meaning of the word ‘Parthenon’ until one has actually seen the thing.”

“Yes, but at least I’ve seen photographs of the Parthenon; I’ve read descriptions.”

“You’ve read descriptions of timeless good,” Mr. Propter answered. “Dozens of them. In all the literatures of philosophy and religion. You’ve read them; but you’ve never bought your ticket for Athens.”

Aldous Huxley, After Many a Summer, 1939

“Pause awhile as you pass by, close your eyes and remember”(Holocaust Memorial in Athens), photo 30 x 40cm.

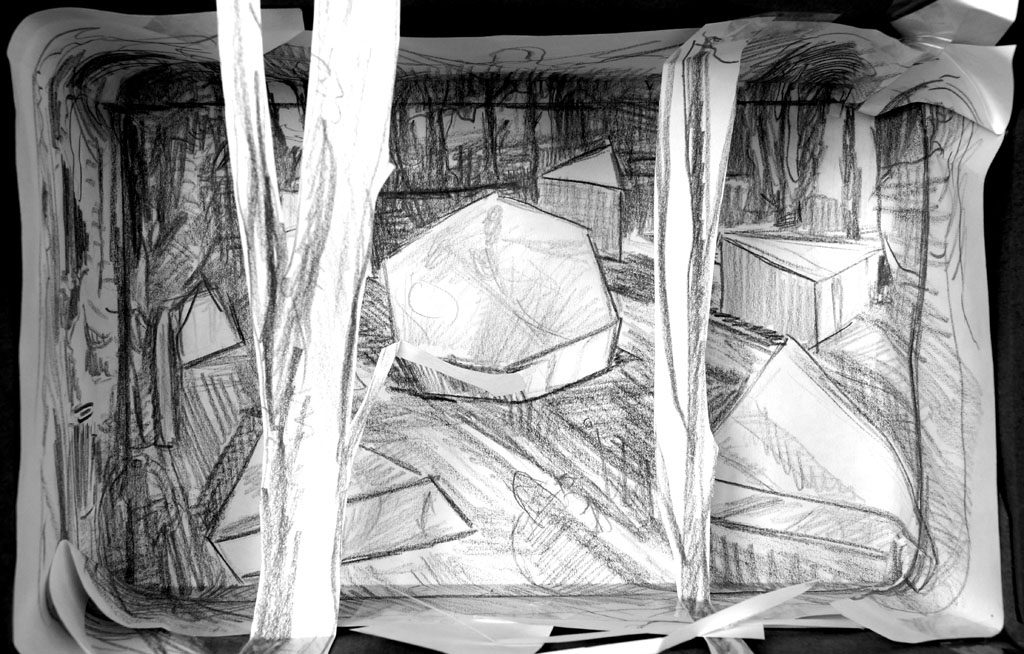

“Rhetoric at Breakfast (PNYX)”

A table is set for an everyday meal. The tableware includes a plate that looks like a souvenir from Greece, with the hillside of Pnyx drawn upon it (cl. Greek Πνύξ; mod. Greek, Πνύκα). It was a place where the Ecclesia, the popular assembly of the democracy of ancient Athens, convened and its speakers would carry on heated debates. Gottfried Benn sought references that would legitimize the authority of the Third Reich and believed he’d found them in the culture of Ancient Greece. Benn, like many of those who despise democracy, was devoted to finding a historical context to justify the violence acted out by the elites, as well as the fascination with the Phalangite soldiers (sexually as well) and, ultimately, the proliferation of an anti-feminist ideology.

Along the edge of the plate, I applied a traditional meander border, but using the pattern of a swastika instead. The table and its place settings are a reference to a sphere of meeting and socializing, rather than to general consumption overall.

Jacques Rancière wrote about the need to look back to the original scandal that was the ‘rule of the masses’ and to capture the complex links between democracy, politics, the republic and representation. This is the price that has to be paid for rediscovering, beyond the now-frigid passion of yesterday and the hatemongering of today, the democratic idea, which is a subversive power, always new and always under threat (from Haine de la démocratie, 2005).

Rhetoric at Breakfast (PNYX)”, 2017, oil on canvas, 130 x 200 cm