Rosemary and Marjoram

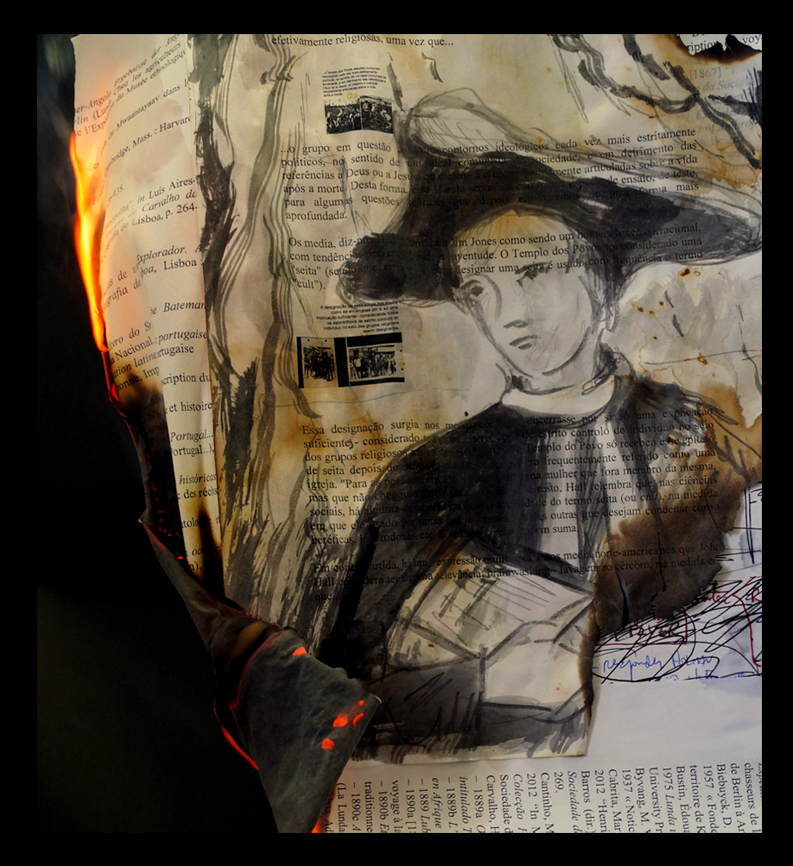

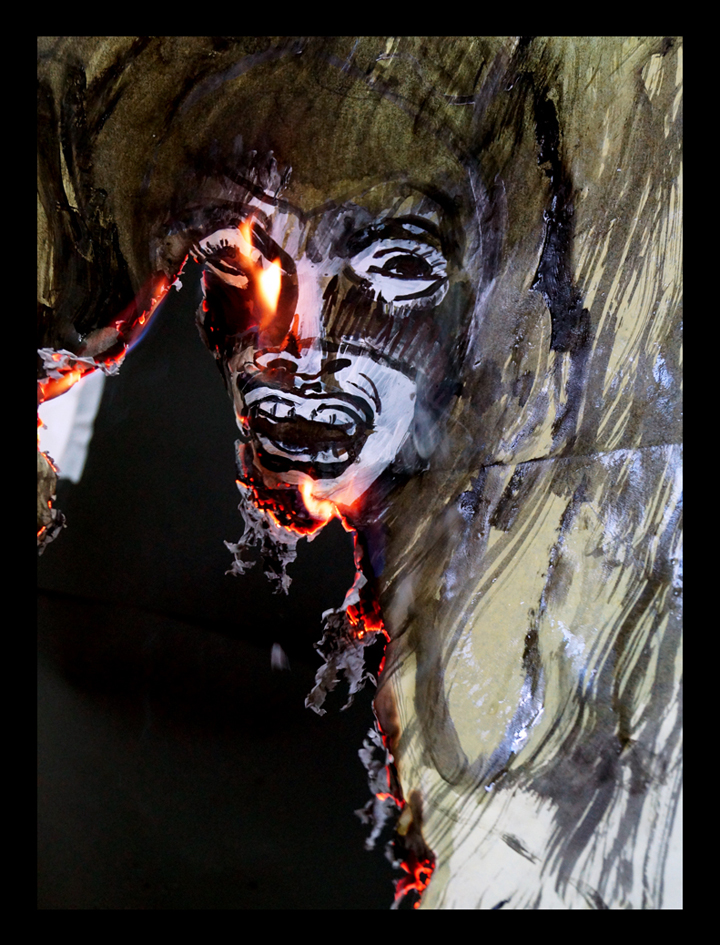

Autodafé Nr 40 (Antonio José da Silva, the Jew), 2018, photo of perfomative drawing, 24 x 22cm.

In July 2018, while in Portugal, I went to an 18th century palace to watch a classic play of 1737, The Wars of Rosemary and Marjoram (Guerras do alecrim e manjerona). A witty, burlesque, satirical piece of theatre by António José da Silva (1705-1739), with baroque operatic scenes by António Teixeira (1707-1774), the whole performance being doubled by a puppet show, in respect to the playwright’s original idea. The experience was expected to be a pleasant, even amusing one, until the moment when the director of the show, with repressed tears in his eyes, recalled that António José da Silva, also known as “o Judeu” (the Jew), was tortured and eventually burnt alive by the Inquisition, accused of following the forbidden religion of his ancestors. His huge success at the time, his fame at the court itself did not prevent the tragic outcome; even king John V attended the auto da fe.

Autodafé Nr 41 (Inquistion spectacle), 2018, photo of performative drawing,28 x 18cm.

A few days earlier, I had visited the church of Saint Dominic, in Lisbon, without knowing that it was the exact place where “the Jew”, dressed as a condemned man, with flames and little devils drawn in his garment and a pointy hat, had to listen to the accusatory sermon for long hours, before the procession and the bonfire. How ironic that the church itself (the one reconstructed after the 1755 earthquake) was consumed by fire in the 20th century – and never again restaured to its splendour. Today, one can still see its marble columns, its whole interior, in black. Outside, a memorial stands to the memory of the jewish victims of the Inquisition, particularly of a “massacre” that occurred in 1506.

This story overwhelmed me, but it also ignited my imagination.

“We often associated science with the values of secularism and tolerance. If so, early modern Europe is the last place you would have expected a scientific revolution. Europe in the days of Columbus, Copernicus and Newton had the highest concentration of religious fanatics in the world, and the lowest level of tolerance. The luminaries of the Scientific Revolution lived in a society that expelled Jews and Muslims, burned heretics wholesale, saw a witch in every cat-loving elderly lady and started a new religious war every full moon.”

Yuval Noah Harari, Homo Deus. A Brief History of Tomorrow, 2015

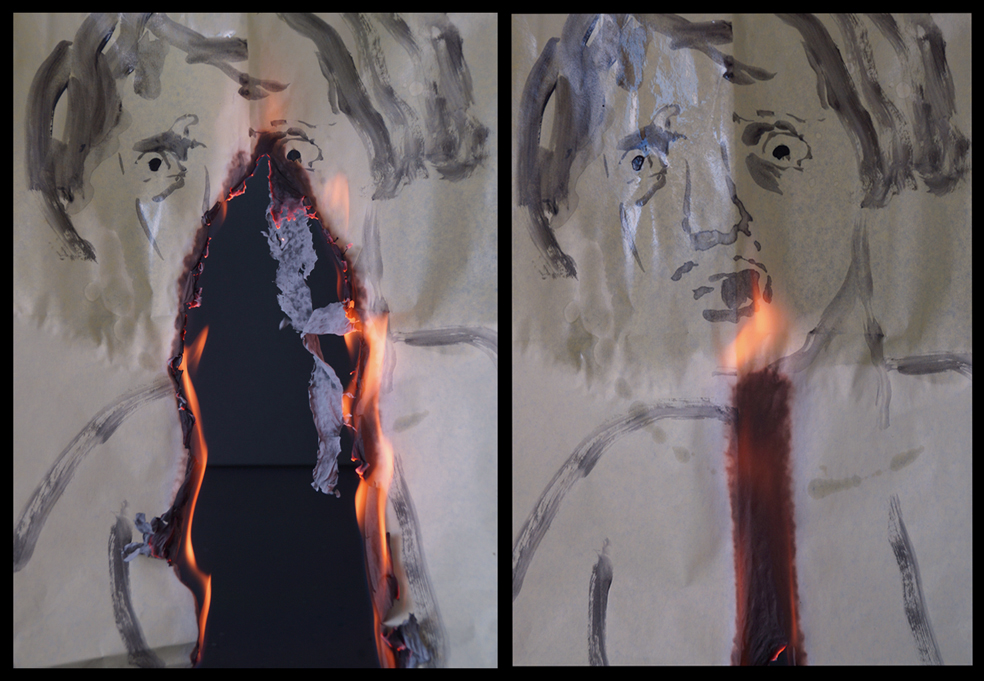

Autodafé Nr 26A,B (Naked Fear), photo of performative drawings, edit.on Murakami paper, 30 x 40cm each.

“The witch-craze is an important study in human evil, comparable to Nazism and Stalinism in the present century. (…) This mania, this eagerness to torture and kill human beings, persisted for centuries. Perhaps we put the wrong question when we ask how this could be. The past half-century has witnessed the Holocaust, the Gulag Archipelago, the Cambodian genocide, and secret tortures and executions beyond number. The real question is why periods of relative sanity, such as those from 700 to 1000 and from 1700 to 1900, occur.”

Jeffrey B. Russell, A History of Witchcraft, Sorcerers, Heretics, and Pagans, London, 1980

Autodafé Nr 37 (Word of Man), 2018, photo of performative drawing, 20 x 35cm.

When the church of Saint Dominic was consumed by fire, back in 1959, Portugal was a nationalistic, fascist-type dictatorship, with dictator Salazar in power since the 20s. His opponents were sometimes called, among other things, “defensores de heresias” – defendants of heretical ideas. (Luís Reis Torgal et al., História da História em Portugal, 1996) A mere metaphor? Cardinal Cerejeira, one of the main supporters of Salazar’s regime, made some interesting reflections on the persecutorial past of the Portuguese Church, namely on the infamous Tribunal do Santo Ofício (Holy Office), the official name of the Inquisition. In his pretension to interpret the spirit of the time, he said that back in the 16th century (when the Holy Office was created) the idea of tolerance did not exist in the same way and added the following note: “(…) the truth is that the Holy Office did not persecute scholars nor men of letters, but only heterodox opinions that had not to do with science nor with artistic or literary genius.” (as quoted in Torgal et. al, 1996). Portugal was, after all (in the 16th as in the 20th century…) a Catholic nation, anointed by God, with predestined heroes and a mission to accomplish.

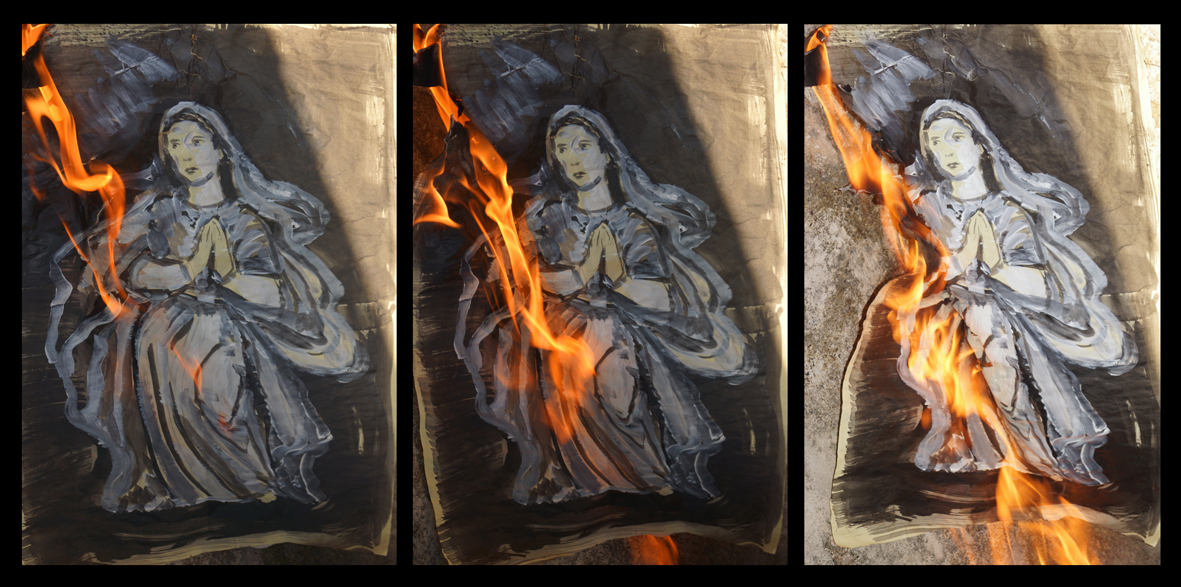

Autodafé Nr 17 A,B,C (Jeanne of Arc’s Truth ), 2018, photo of performative drawing, 30x40cm. edit. on Murakami paper.

When he was 8 years old, Antonio José da Silva and his father left Brazil following the deportation of his mother to Lisbon, accused of Judaism. Other members of the family, a brother, an aunt, even his pregnant wife, were victims of the Holy Office.

Audodafé Nr 12 D(Jeanne of Arc’s ) , 2018, photo of performative drawing, 30x40cm,edit. on Murakami paper.

Autodafé Nr 42 (Fals Accusation), 2018, photo of performative drawing,40 x 30 cm.

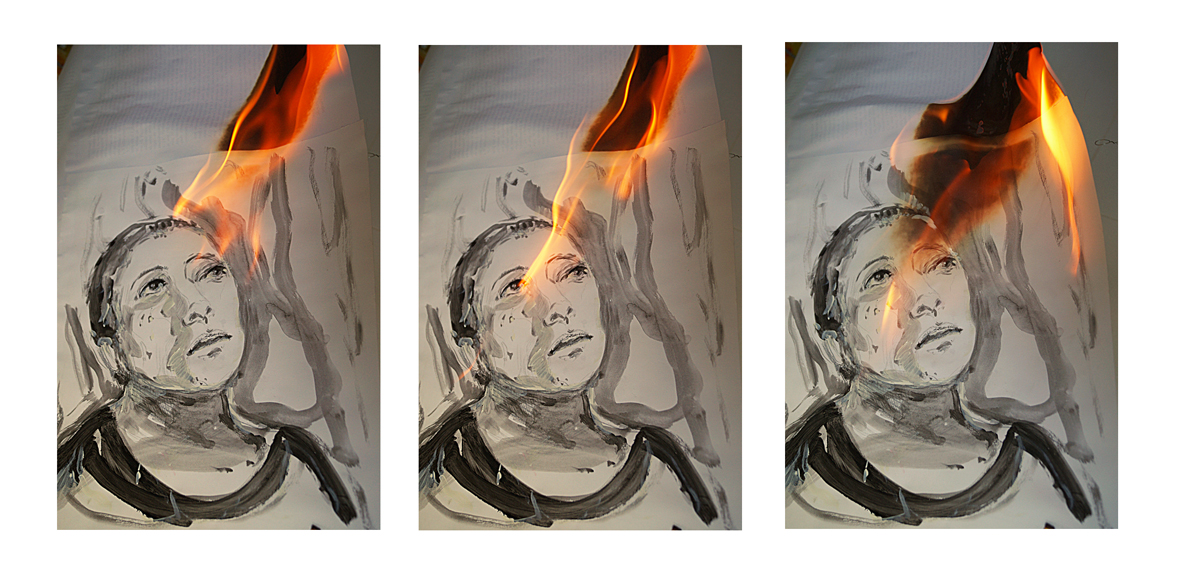

Autodafé Nr 43 A,B,C ( The Truth Body), 2018, photo of performative drawing,30 x 40 cm each.

In 2017, during a trip to Andalucía, I entered an academic bookshop in Granada and looked for a book on the history of Spanish Inquisition. I couldn’t find any and asked the bookseller for help. To my surprise, she answered: “You won’t find any, nor here, not anywhere”. As if I was asking for some filthy pornography.

“Here’s something no one expected: A reputable conservative magazine has published a column defending … The Spanish Inquisition. To be clear, this is not Monty Python. This is a column in the National Review. Here’s the headline: “The Spanish Inquisition Was a Moderate Court by the Standard of Its Time.” Moderate? (…) let’s read some of the takes from the column, written by Ed Condon, identified as a writer, editor and practicing canon lawyer. ‘[W]hile any reasonable person would find a lot not to like about the Spanish Inquisition,’ writes Condon, in perhaps the understatement of the year, ‘in fact, examined simply as a functioning court, the Spanish Inquisition was in many ways ahead of its time and a pioneer of many judicial practices we now take for granted. Let’s start with the basic legal concept of an ‘inquisition,’ he continues. ‘It just means a court of inquiry in which the judges take the lead in directing proceedings in the pursuit of truth, rather than a prosecution-driven adversarial system. Such courts continue to function in many secular jurisdictions today, and there is, frankly, nothing very sinister about it, though it appears alien to those of us raised on American courtroom dramas.’ (…) He writes that the Inquisition courts were fairer than Spanish civil courts. That last point may very well be true, but … who cares? During the Inquisition, which wasn’t abolished until the early 19th century, hundreds of thousands were forced into exile, and thousands were converted under duress. Tens of thousands more were murdered. It was a reign of terror that persecuted people based on their religion and, significantly, their race. Even pious Catholics with Jewish roots were targeted. It struck fear into an entire population that was already forced into secrecy.”

Ben Sales, JTA (Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Jta.org), 2018

Cordoba Alcatraz, 2017, photo, 25 x 28 cm.