Sleepless Melville

“The greater the fog, the more it imperils the steamer, and speed is put on though at the hazard of running somebody down. Little ween the snug card players in the cabin of the responsibilities of the sleepless man on the bridge.” Herman Melville, Billy Budd, Sailor, 1924

“[Pathos is] the very concept of duplication, of irreducible difference, of possible drama, of what escapes the concept.”1

- Meyer, “Postface”, in Aristotle’s Rhetoric, cit. in Massimo Olivero, Figures de l’extase. Eisenstein et l’esthétique du pathos au cinéma, 2017

Billy Budd, Teatr Wielki, general view.

While preparing a show inspired by Benjamin Britten’s Billy Budd, on the occasion of its premiere at the Great Theatre – National Opera House in Warsaw, I was mesmerised by the symbolic complexity of both the libretto and the original 1924 short novel by Hermann Melville…I wanted to modernise the ship “Rights of Man” mentioned in Melville’s novel as the merchant ship which the young sailor leaves when press-ganged into service on the warship “The Bellipotent”. Melville paid metaphorical tribute to the ideals of the French Revolution, and in the E. M. Forster’s and Eric Crozier’s libretto, British monarchy fights against progressive ideas. It appears that the ship “Rights of Man” belonged to a wealthy ship owner, one of the fathers of capitalism in the US, who made a huge fortune during the American Civil War.

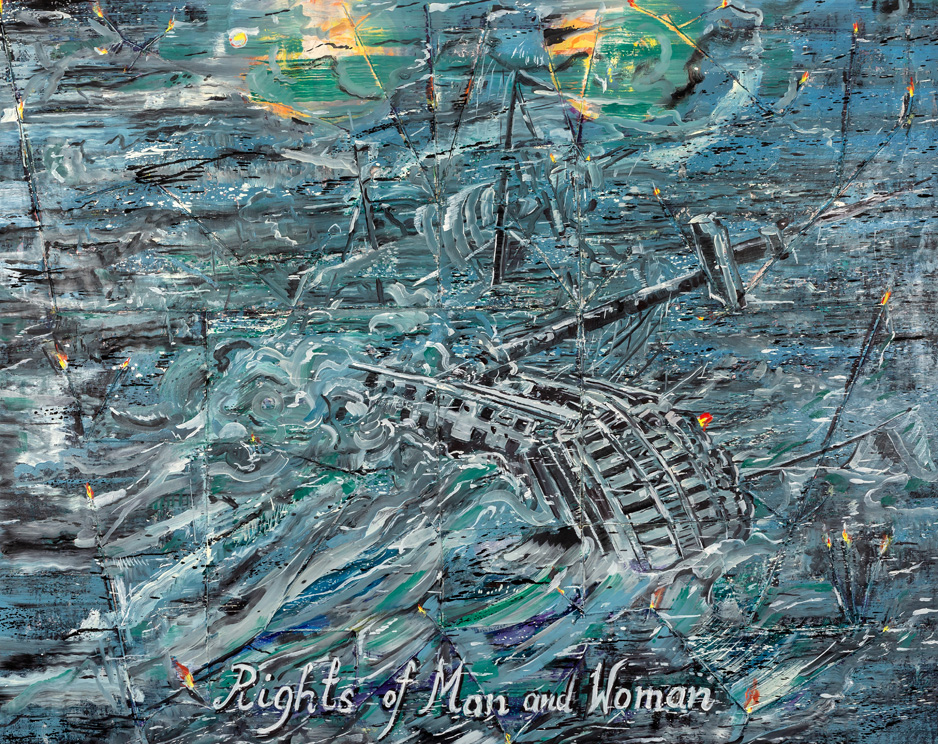

Shipwreck,2019, oil on canvas and strings, 160 x 200 cm. Photo Teatr Wielki.

In the painting Shipwreck, where the ship is renamed “Rights of Man and Woman”, the oil technique and ropes sewn on the canvas combine both uncertainty and detachment, an apparently historicising scene – with its precise figurative elements of the marine tradition – with an informal “ocean of pictoriality”, bringing forth contemporary issues and conflicting notions of order and chaos, violence, detachment and pathos.

Shipwreck, detail.

“The Pathetic […] is a conceptual oxymoron allowing Eisenstein to conceive the possibility of going beyond the representation while remaining within it. He then hypothesizes that the work of art, which is an artificial body thanks to the violent action of pathetic forces determining a process of metamorphic alteration, can emerge on its own to become other than itself. It is in this process of opening up the natural organic structure that comes the Subject’s creative action, which plays a decisive role in the construction of the new organism. It is thanks to this action that Nature will become precisely non-indifferent by allowing the new body to reach a qualitatively higher level, the ecstasy of full communion subject-object, man-nature, work of art-reality, idea-world.”

Massimo Olivero, Figures de l’extase. Eisenstein et l’esthétique du pathos au cinéma, 2017

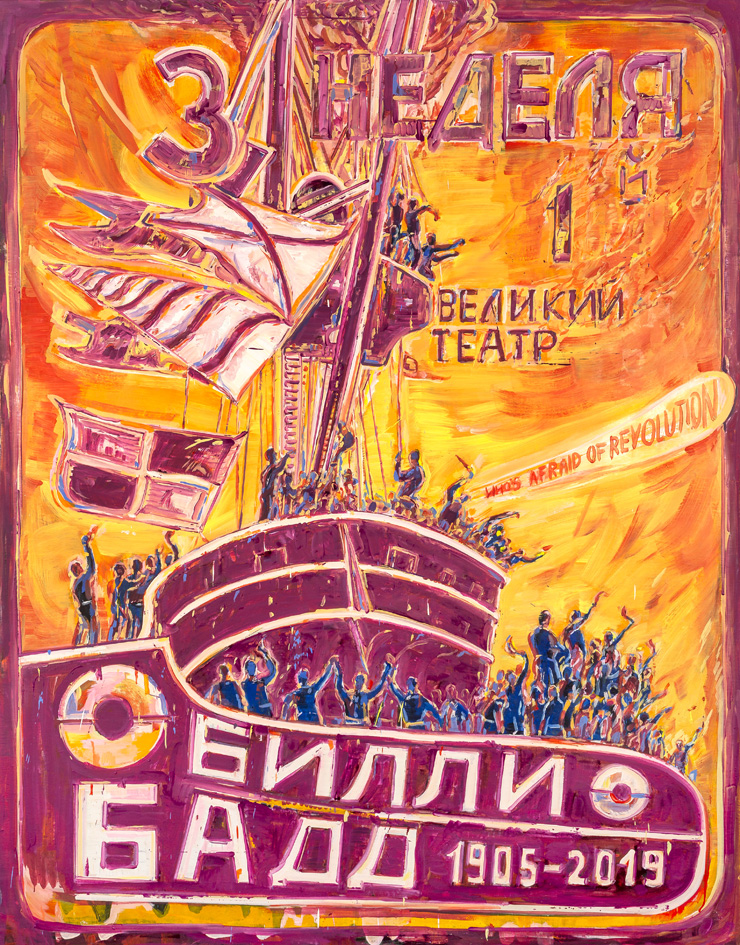

How do the colours of flower power and the hippie revolution transform the poster for Sergei Eisenstein’s film Battleship Potemkin (1925)? Who is afraid of the revolution? For whom is it liberating and for whom is it a threat? Comic-book-inspired, does the painterly treatment distract or dedramatise the sailor revolt against tsarist command during the failed revolution of 1905? Does it make it possible to regain a critical distance from tsarist violence or from Soviet propaganda?

Potemkin and Billy Budd at the Grand Theatre, oil on canvas, 210 x 165 cm. Photo Teatr Wielki.

“A performative painting, with parts destroyed by fire, combines the movements of a rebellious crowd – people fighting for their rights or a mob searching for a confrontation with the forces of order? – with anachronistic characters such as Marie Antoinette inside her coach, Vladimir Putin riding a bear, or an anonymous woman suspended from a street lamp as a contemporary Marianne. How many times have I myself experienced similar dramatic situations in the streets of Warsaw and Paris…” Adam Adach, 2019

Helmets and High Visibility Vest, 2019, oil on canvas, 130 x 200 cm. Photo Teatr Wielki.

Helmets and High Visibility Vest, detail.

“Gemütlichkeit is the mask that hides a ressentiment against the world – any world.” Sebastian Zeidler, Form As Revolt. Carl Einstein and the Ground of Modern Art, 2015

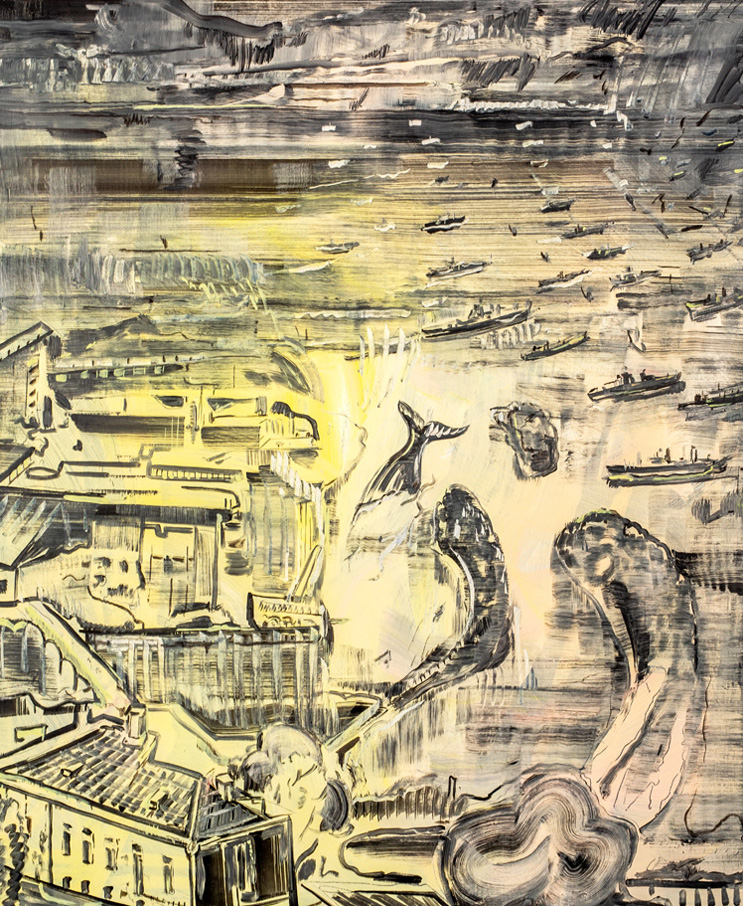

Moby-Dick, 2019, oil on canvas, 155 x 130 cm.

Is Moby Dick a theological or an ecological treatise? Hunting a white whale, or chasing God? A conceptual collage portrays the quays of invisible sailors whose lives around the world are memories of a global landscape, including the port of Odessa, where the battleship Potemkin was moored, or the North Pacific waters during the US-Japan war.

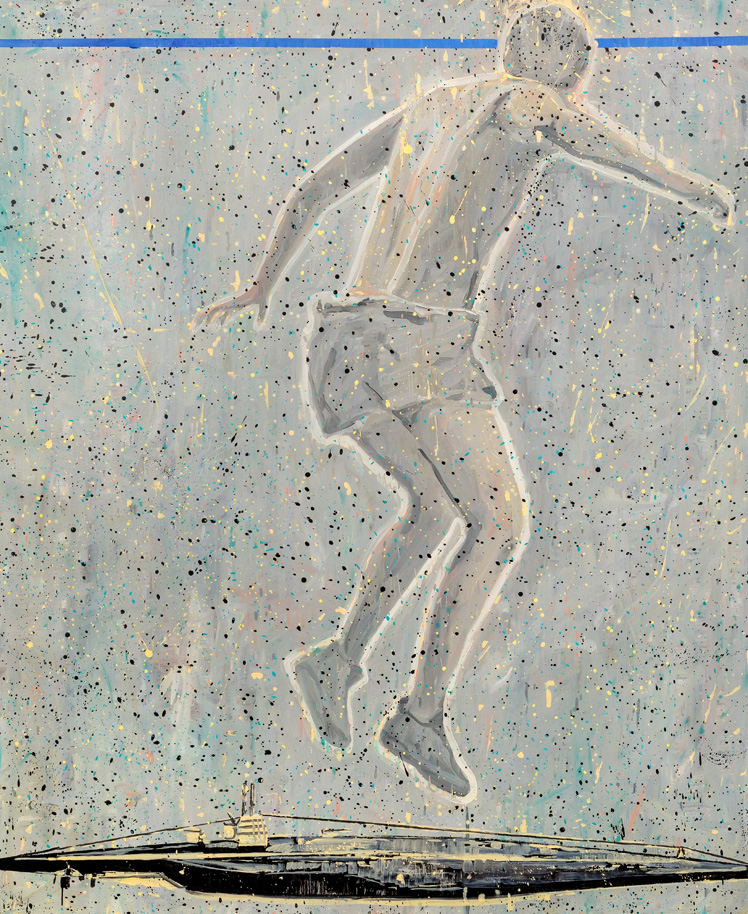

Run a Risk, 2019, oil on canvas, 170 x 140 cm. Foto Opera Narodowa

To what extent is it liberating to enter a dangerous situation? To what extent is it necessary? It was the last second of his life. A jump into deep water. A boy whose friends photographed him as he jumped into the water – somewhere in the port of Brighton. He jumped wrong and hit a sunken log.